Applications

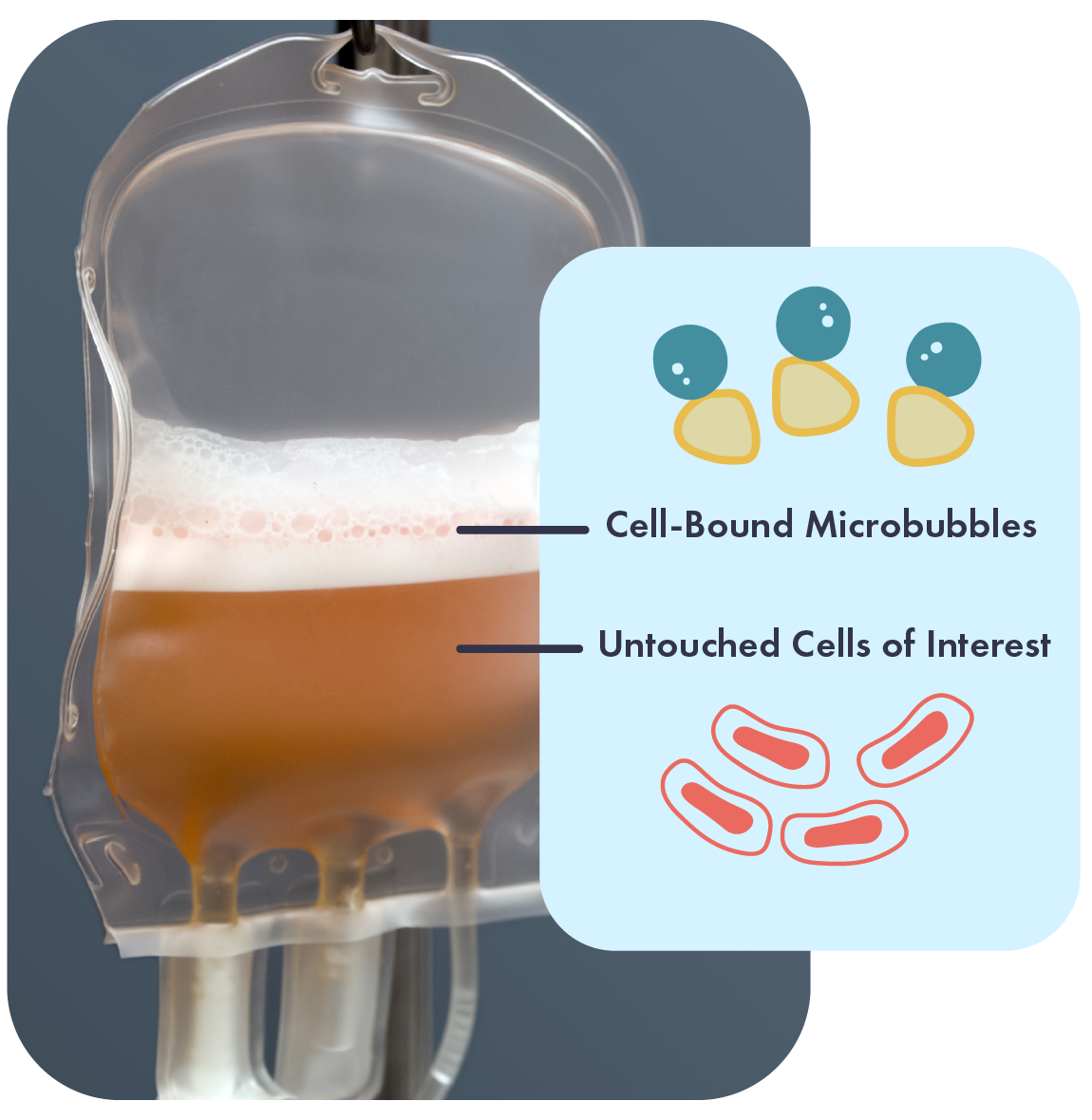

Akadeum’s microbubbles are an innovative approach to separation technology that’s disrupting the status quo.

At Akadeum, we seek to improve human health by enabling better cell separation processes. We are revolutionizing the way separations are performed, including cell separation, nucleic acid extraction, chemical separation, and so much more. The power of our platform is that we’ve developed an elegant and easy-to-use technology that can enable faster, more accurate, and scalable workflows to solve the problems of tomorrow.

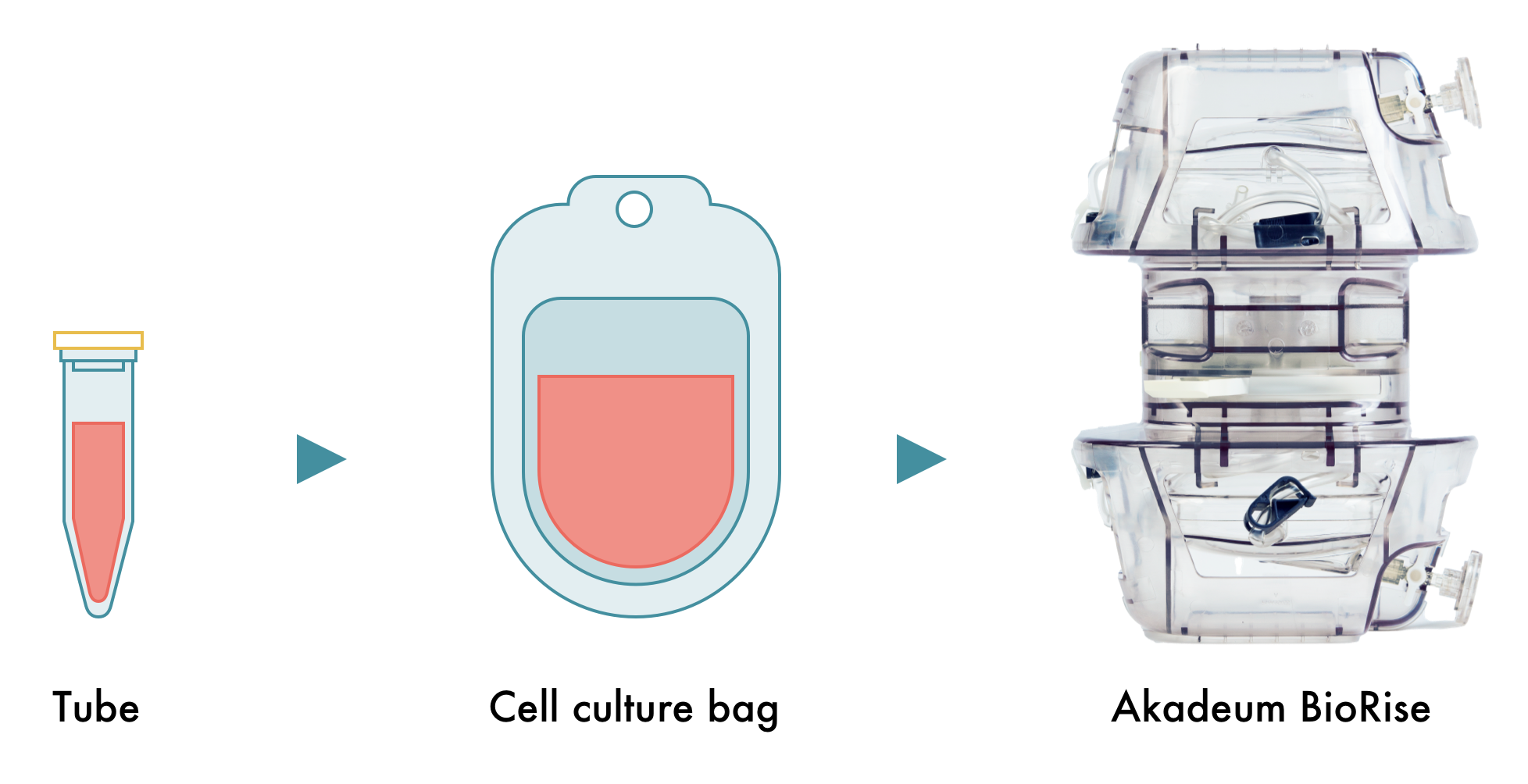

Closed System In-bag Cell Separation with Akadeum’s Microbubbles

Published on Apr 22, 2025 Share

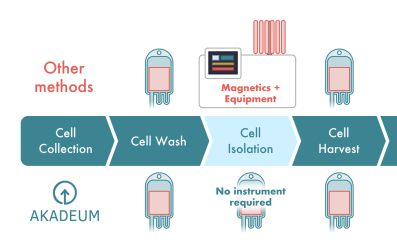

In this app note, learn how Akadeum’s closed-system, in-bag cell separation technology enables high-performance T cell isolation directly from apheresis material without preprocessing or complex equipment. This streamlined method maintains viability, purity, and yield up to 72 hours post-collection, making it ideal for cell therapy developers seeking efficient, reproducible starting material for CAR T manufacturing.

Next Generation Cell Isolation –Scalable Negative Selection Integrated into your Current Workflow

Published on Apr 7, 2025 Share

This app note explains how Akadeum’s microbubble technology offers a modern, scalable solution that integrates seamlessly with existing workflows and instrumentation. Akadeum’s closed-system, modular workflows allow researchers to work with healthier cells, improve efficiency, and reduce cost. Cell isolation on any sample, any system, anywhere.

High Purity T Cells and Reduced Key Impurities With Akadeum Microbubbles: An ElevateBio Study

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

Akadeum’s Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit was more effective at isolating cells than magnetic methods in ElevateBio’s CAR-T workflow. Read the app note to see how ElevateBio achieved high-purity T cells while reducing key cellular impurities. This led to improvements in overall cell therapy workflow efficacies and efficiencies. Key Data: Higher purity than magnetics and Improved removal of undesired cells.

End-To-End Production of T Cells on Lonza’s Cocoon Platform

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

View performance data in this app note for the Cocoon® Platform while using Buoyancy-Activated Cell Sorting™ for T cell isolation, directly from cryopreserved leukopaks, with: No additional upstream equipment required, reduced operator interactions, flexibility of activator enabled by negative selection enables, recovery of ~64% of CD3+ cells with ~92% purity, and expansion to ~2.6×109 T cells in 9 days.

Unmatched Scalability, From Process Development to Manufacturing

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

As your cell therapy workflow scales from research to commercialization, Akadeum’s technology is poised to scale with you. From small 50 million cell experiments to tens of billions of cells, performance and viability is maintained while time decreases.

Microbubble Performance with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Donor Material

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

Enhanced purity and yield of CD3+ T cells was achieved using Akadeum’s Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit and sample material from a donor diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who has undergone multiple rounds of chemotherapy. Higher capture efficiency observed with Akadeum’s Human T Cell Selection, Activation, and Expansion Kit demonstrates a more effective recovery of viable T cells compared to magnetics.

Best Practices With Starting Materials for the Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit

Published on Feb 11, 2025 Share

Guidance for adjusting protocols for Akadeum’s Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit to fit your needs. This kit offers a fast, scalable, and efficient method for isolating highly pure, viable T cells. Works with fresh, cryopreserved leukopaks, and PBMCs Simple protocol adjustments optimize purity and yield Negative selection method ensures untouched T cells for research & therapy

Optimizing the Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit for Cell Type of Interest

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

Discover how to optimize your T cell isolation with Akadeum’s Human T Cell Leukopak Isolation Kit. Using innovative buoyancy-based microbubble technology, this kit delivers highly pure T cells while allowing customization for specific cell types and experimental conditions. Enhance efficiency without compromising performance.

Akadeum and the G-Rex System: A Positive Selection Method for Highly Activated, Less Exhausted Cells

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

Isolation and activation of T cells with Akadeum’s Human T Cell Selection, Activation, and Expansion Kit can be complemented with expansion of the cells on the Wilson Wolf G-Rex® culture system. In this app note we demonstrate how the combination of the microbubbles and G-Rex® system promotes cell health and expansion while causing less cell exhaustion than magnetics.

Dead Cell Removal (DCR) With Microbubbles

Updated on Feb 12, 2025 Share

Dead cells are a common contaminant, and their presence can lead to any number of negative downstream impacts, including poor sort efficiencies, extended sort times, and an overall reduction in purity. Akadeum’s microbubble platform is uniquely well-suited for the targeted depletion of dead and dying cells while maintaining the health and physiology of live cells and other delicate analytes of interest.